Case 27

| Case Number | 27 |

| Charge | Assault |

| Defense Attorney Present | Yes |

| Interpreter Present | Yes |

| Racialized Person | Yes |

| Outcome | Prison |

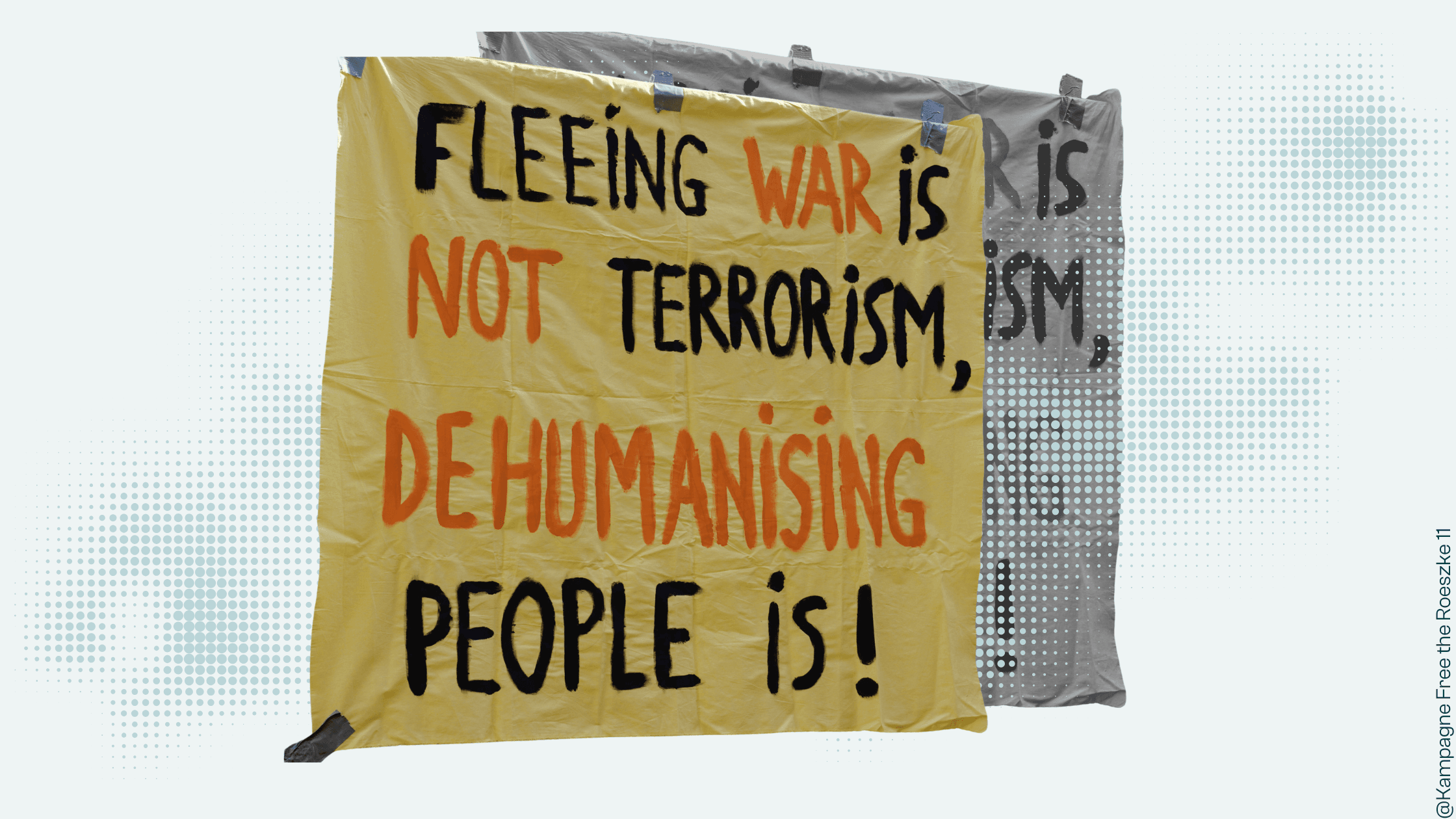

Shortly after a wave of populist outrage over a knife attack, a man convicted of attempted assault with a weapon based on little evidence appeals his sentence. At the appeal hearing, the environment is hostile, with the recent knife panic in the air: the defense is hindered from questioning witnesses while the judge and prosecutor cherry-pick testimony in an effort to justify continuing to jail the defendant pretrial, which would also facilitate his deportation. Even after a second appeal hearing does not reveal evidence sufficient to convict, the judge and prosecution insist on a high prison sentence, just two months short of his original one. The defendant is released after the second hearing because he has already served his sentence in pretrial detention.

The appeal starts shortly after public outrage over a knife attack fuels racist sentiment towards asylum seekers and renews calls for increased deportations. This case shows that the courts are not exempt from populist “migrant crime” narratives and are willing to forego legal and procedural principles when they want to convict someone harshly. In this case, the court was eager to set an example, and to hold the defendant for as long as possible pretrial to facilitate his deportation. With very little evidence, the defendant was accused of assault with a pair of scissors. Against the backdrop of his application for asylum having been denied, the case resonated with moral panics seeking to establish a connection between migration and “knife crime”. So far, the state had been unsuccessful in deporting the defendant, who had Duldung status, because of unclear documentation of his citizenship. From what we learned, the judge communicated with migration authorities before the trial, who indicated they may soon have their paperwork in order to deport the person. Carrying out the deportation would be much easier if the defendant could be picked up from jail, and the judge and prosecution made efforts to facilitate this.

The victim of the alleged assault is absent from the proceedings, leaving crucial questions unanswered including whether there was a wound, who did what to whom, what sparked the fight, or whether a weapon was even involved. The court has three witnesses: a passerby, an acquaintance of the victim, and a person who interpreted for the police and observed little of the actual incident. Based on their testimony, the court’s version of events is that a fight between two men broke out in a dispute over money. In the court’s narrative, the defendant pulled a weapon from a backpack and injured the victim. The defense appealed the court’s decision because the court’s conclusions were not supported by the testimonies.

Several lawyers who reviewed this case agreed that the evidence brought against the defendant was insufficient for a conviction, and that the extended pretrial detention was clearly disproportionate. As the defendant conveyed to us and to his counsel, he was impacted by being held in prison with no certainty over when he might be released, by experiencing over and over the extension of his incarceration because of procedural issues, and by seeing fellow incarcerated people coming and leaving pretrial detention before him.

Before the Trial

This case is an appeal of a lower court’s decision to sentence a man to over a year in prison with very little evidence. By the time this appeal begins, he has already spent nine months in pretrial detention, where he receives no visitors except for his lawyer. He was convicted of attempted assault with a weapon following a fight at a bar.

The first hearing is delayed, prompting the judge to approach a witness in the hallway to inform him of this. The witness appears visibly irritated and tells the judge that so much time has passed that he is uncertain about what he can still remember about the day. The judge assures him that his testimony will be valuable to the case, taking him aside to suggest that “surely he will remember something of relevance.”

First Hearing

From the outset, the proceedings are marked by judicial hostility and an aggressive courtroom atmosphere. The judge starts by skeptically questioning the defendant’s name and citizenship, even arguing that his place of origin is not legitimate because she cannot find it on Google Maps. She insists that she knows his citizenship, despite the authorities officially registering him as “stateless.” Her harsh demeanor extends to both the defendant and his lawyer, whom she reprimands repeatedly for attempting to correct their client’s personal details on file with the court.

The judge’s treatment of the first witness is in contrast to her treatment of the defendant and his lawyer. The judge asks him suggestive questions rather than examining his statements critically. The witness testifies that he saw a group of “North African citizens,” including the defendant, physically fighting in front of a bar, approximately 100 meters away from where he was standing. He alleges he saw a weapon, though he cannot describe what it looked like, and says he witnessed a stabbing motion, prompting him to call the police. He admits that he did not continue observing the fight as he was occupied with the police and cannot remember many details of what happened. He says the event was traumatizing for him. The judge expresses sympathy, reassuring him that calling the police – and testifying against the defendant – was the right thing to do.

When the defense takes a more critical approach to questioning, the judge accuses them of putting the witness through unnecessary trouble and interrupts the hearing twice. As the defense tries to highlight inconsistencies in the witness’s statements, they are loudly reprimanded, interrupted, and talked over by the court actors. Encouraged by the judge’s behavior, the witness refuses to answer questions to clarify contradictions in his testimony – such as whether he saw a weapon at all, whether he saw someone falling or getting injured, or any physical descriptions of the alleged suspects beyond their perceived place of origin. Instead of explaining the importance of these details for evidence collection, the judge allows the witness to evade questions and even joins in laughing at inappropriate jokes while ridiculing the defense for wasting time.

The second witness – who had previously reported seeing scissors and a stabbing – now fails to recall these details, causing the judge to become visibly frustrated. He was friends with the victim and part of the group who had been drinking at the bar earlier. The witness had initially told police that the defendant stabbed the victim with scissors but now testifies that he may have imagined this. He explains that he was very drunk that night and does not remember why he told police he saw a weapon. Instead of weighing this admission in favor of the defendant, the judge and prosecution question whether the witness “usually” lies to authorities and cast doubt on how drunk he really was, seemingly holding on to his initial, more incriminating statement.

As the defense’s questioning reveals that the witness initially gave a contradicting statement, the judge does not take notes or pay attention. Instead, she suddenly fixes her attention on the court-watchers, forbidding them to take notes word-for-word and even instructing the guards to review the notes. This sudden disruption distracts from the testimony.

The final witnesses are the police officers who were called to the scene. The officers admit they did not find a weapon at the scene, confirming their initial report. They also say that they were unable to identify the defendant as the perpetrator.

Second Hearing

The trial continues, beginning with the prosecution’s key witness, a doctor who briefly interacted with the victim on the day of the alleged offense. Because he helped the police communicate with the victim on the day of the alleged offense, he is one of the only witnesses that can speak to the victims injuries, if any. At trial, the witness testifies that he saw a pair of scissors, the alleged weapon, on the floor in front of the venue but cannot confirm whether they belonged to the defendant, resulting in brief speculation whether they may have belonged to the venue. He did not see the fight, and only got involved once the police arrived.

The defense questions whether the witness and the victim shared a dialect, to evaluate how reliable his role in translating for the police could have been. Although their dialects are vastly different, the judge insists that the witness claims to have understood the victim, which she considers sufficient evidence.

Language barriers become a central issue as the defendant struggles to understand both the interpreter and the witness due to significant dialect differences. Despite this, the judge insists on proceeding, dismissing the defense’s concerns. Instead of addressing the interpretation problem, she blames the lawyer for the communication breakdown. When the lawyer attempts to clarify with her client by using a mix of languages, the judge makes a dismissive remark, stating that their communication “seems to work well enough without an interpreter,” implying that the lawyer, who is also racialized, could simply serve as the interpreter.

During continued questioning without adequate interpretation, the witness confirms that they had a phone call with another witness before the first trial to discuss their testimony because they did not remember much. When the defense requests a pause to discuss the language issues, a heated debate erupts between the judge and the lawyer, turning into a shouting match audible outside the courtroom. The defense, trying to defend her client’s right to interpretation, is shouted over by the judge, who says the lawyer is attempting to delay and disrupt the hearing.

As the proceedings continue, the judge urges that they wrap the trial that day, saying that the defendant is signaling with his eyes that he also wants to finish. She accuses the lawyer of working against her client’s interests by insisting on proper interpretation. She further claims to have received information from authorities confirming that the defendant understands the dialect.

Another hearing is needed to ensure the rest of the evidence and plea procedure are translated for the defendant in a language he understands. The defense requests the release of their client from pretrial detention, which would spare him from further incarceration while awaiting the next hearing. However, the judge quickly dismisses this, stating simply, “Haftentlassung geht nicht” (release is not possible). She argues that the defendant poses a flight risk since he is an asylum seeker with no stable social ties in Germany. She concludes that continued incarceration is proportionate. Despite the urgency posed by the defendant’s imprisonment, the trial is postponed for two months because of court staff’s vacation schedules. Because the delay is longer than permitted by trial rules, the trial must be restarted from the beginning.

Third Hearing

Months later, the trial starts over. The only new addition to the court is a second defense lawyer. The judge attempts to remove the defendant’s primary lawyer, arguing that having a second lawyer present raises the costs to the state.

The defense proposes a plea agreement (Verständigung) for a 12-month sentence – time already served – which is accepted by the court.The sentence is just short of the defendant’s original sentence.

Before concluding, the court again reviews personal details about the defendant, including the correct spelling of his name and his citizenship status. The judge passingly notes his qualifications and good conduct in jail and reads the defendant’s prior convictions. She reads from the Foreigners’ Central Register (Ausländerzentralregister), detailing that the defendant’s asylum application got denied. She adds that he “came to Europe by boat”. The defendant is asked about his plans after release from pretrial detention. When he expresses his desire to continue his apprenticeship, the judge immediately references his record in the register, emphasizing that his deportation has already been ordered but not yet carried out.

The defendant is released from prison, effective immediately, after one year of pretrial detention.